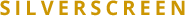

Martin Armstrong’s career thus began with a complete error of judgement. Even at this young age, he tried to understand the system, to grasp the logic according to which each boom was followed by a bust. Was Niccolo Machiavelli right in his belief that history repeated itself because man’s passions remain the same? He analysed the financial markets, studied the history of business cycles, stock market crashes and global monetary systems. He visited libraries and collected historical data: gold prices, exchange rates. He played around with figures and dates, he divided the time span between the Rye House Plot in 1683 and the year of the bankers’ panic in 1907 (224 years) by the number of market crashes during this period (26) and ended up with an average of 8.6

Eight point six – the global economy appeared to be based on this 8.6-year cycle. He multiplied the cycle by six which gave him 51.6 years and once again it all fitted perfectly: Black Friday in 1869, the commodity panic in 1920, and the Second and Third Punic Wars. He divided, subtracted and multiplied and established that 8.6 years equalled three thousand one hundred and forty-one days: 3,141, the magic number pi times a thousand. Did pi perhaps also govern the markets or the actions and moods that manifested themselves in these markets?

Armstrong was sure of one thing: there is a geometry of time. He may not be able to explain why, but there is some order to the chaos that exists around us.

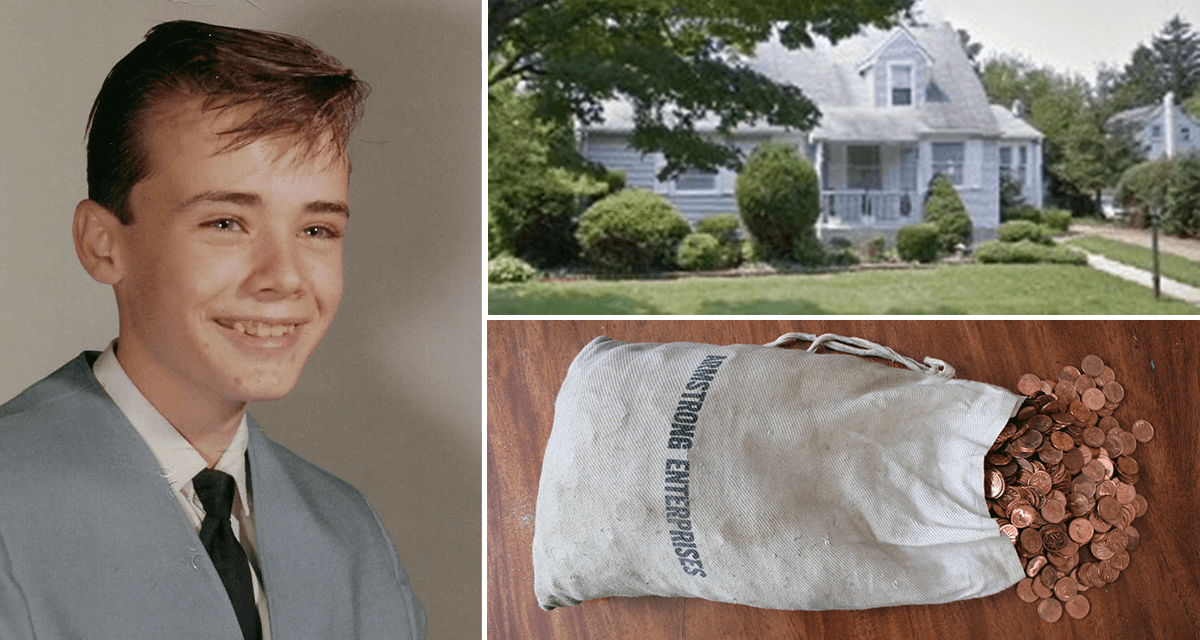

Martin Armstrong had just published the secrets of pi when FBI men stormed his office. Soon his accounts and those of his partners in London, Australia and Japan had been frozen. They were not to meet for twelve years. “Is financier Armstrong a Con man, a crank or a genius” asked the New Yorker headline in an eight-page article written as Armstrong was in a maximum security wing in New York. What are the judicial facts, the legal peculiarities and the juristic doubts involved here? And who could have profited from Martin Armstrong’s lengthy sentence behind US bars? And: what does all this say about a system on which we are all dependent in one way or another?

12 years after the demise of Princeton Economics Martin Armstrong is released from prison after he signed a coerced guilty plead. His new life commences with a “World Economic Conference” in Philadelphia. Only three months after his release, he’s back again. As if nothing had happened. As if there’d been no twelve years where he was deprived of the world. Martin Armstrong lectures to 350 people, who travelled especially to Philadelphia to see him. He speaks of his initial approach towards solving the global financial crisis, which he compares to the fall of the Roman Empire. And twelve years later, some of his former partners are back to perhaps resume operations where they’d left off. Will Martin Armstrong and his former partners join forces and re-establish Princeton Economics to make their distinctive mark on the desolate landscape of the financial sector?